ADVERTISEMENTS:

The landforms created as a result of degradational action (erosion) or aggradation work (deposition) of running water is called fluvial landforms.

These landforms result from the action of surface flow/run-off or stream flow (water flowing through a channel under the influence of gravity). The creative work of fluvial processes may be divided into three physical phases—erosion, transportation and deposition.

Various Aspects of Fluvial Erosive Action:

Running water may carry out erosion through any one or more of the following ways:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

1. Mechanical action may include the solid river load striking against rocks and wearing them down (corrasion or abrasion), or the force of running water wearing down rocks (hydration) or the river load particles striking, colliding against each other and breaking down in the process (attrition).

2. Chemical action includes corrosion or solution.

This action of running water may either be in vertical direction (down cutting leading to valley deepening) or in lateral/horizontal direction (causing valley broadening). The lowest level to which a valley can be eroded by running water is called its base level. J.W. Powell had given the concept of base level in 1875.

The sea level is considered to the Ultimate or Grand Base Level below which a dry-land cannot be eroded anywhere on earth. There may be many temporary base levels during the course of a stream because of a variety of factors, such as at the confluence of a tributary and the master stream, which is the base level for the tributary and presence of a lake or enclosed water body, etc.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Superimposed and Antecedent Drainage:

A part of a river slope and the surrounding area gets uplifted and the river sticks to its original slope, cutting through the uplifted portion like a saw, and forming deep gorges: this type of drainage is called Antecedent drainage. Example: Indus, Satluj, Brahmaputra.

When a river flowing over a softer rock stratum reaches the harder basal rocks but continues to follow the initial slope, it seems to have no relation with the harder rock bed and seems unadjusted to the base. This type of drainage is called superimposed drainage. Examples: rivers of eastern USA and southern France.

Drainage Patterns:

The typical shape of a river course as it completes its erosional cycle is referred to as the drainage pattern of a stream. A drainage pattern reflects the structure of basal rocks, resistance and strength, cracks or joints and tectonic irregularity, if any.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

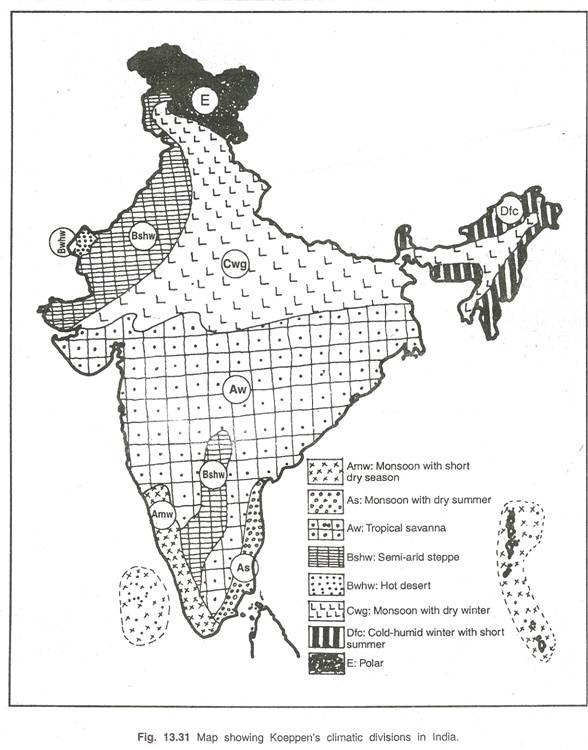

There can be various types of drainage patterns. (Fig. 1.47)

1. Dendric or Pinnate:

This is an irregular tree branch shaped pattern. Examples: Indus, Godavari, Mahanadi, Cauveri, Krishna.

2. Trellis:

In this type of pattern the short subsequent streams meet the main stream at right angles, and differential erosion through soft rocks paves the way for tributaries. Examples: Seine and its tributaries in Paris basin (France).

3. Rectangular:

The main stream bends at right angles and the tributaries join at right angles creating rectangular patterns. This pattern has a subsequent origin. Example: colorado River (USA).

4. Angular:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The tributaries join the main stream at acute angles. This pattern is common in foothill regions.

5. Parallel:

The tributaries seem to be running parallel to each other in a uniformly sloping region. Example: rivers of lesser Himalayas.

6. Radial:

The tributaries from a summit follow the slope downwards and drain down in all directions. Examples: streams of Saurashtra region and the Central French Plateau.

7. Annular:

When the upland has an outer soft stratum, the radial streams develop subsequent tributaries which try to follow a circular drainage around the summit. Example: Black Hill streams of South Dakota.

8. Centripetal:

In a low lying basin the streams converge from all sides. Examples: streams of Ladakh, Tibet, and the Baghmati and its tributaries in Nepal.

Fluvial Landforms:

The landforms created by a stream can be studied under erosional and depositional categories.

1. River Valleys:

The extended depression on ground through which a stream flows throughout its course is called a river valley. At different stages of the erosional cycle the valley acquires different profiles. At a young stage, the valley is deep, narrow with steep wall-like sides and a convex slope. The erosional action here is characterised by predominantly vertical downcutting nature. The profile of valley here is typically ‘V’ shaped. As the cycle attains maturity, the lateral erosion becomes prominent and the valley floor flattens out. The valley profile now becomes typically ‘U’ shaped with a broad base and a concave slope.

A deep and narrow V shaped valley is also referred to as gorge and may result due to downcutting erosion and because of recession of a waterfall. Most Himalayan rivers pass through deep gorges (at times more than 500 metres deep) before they descend to the plains. An extended form of gorge is called a canyon. The Grand Canyon of the Colorado river in Arizona (USA) runs for 483 km and has a depth of 2.88 km.

A tributary valley lies above the main valley and is separated from it by a steep slope down which the stream may flow as a waterfall or a series of rapids.

2. Waterfalls:

A waterfall is simply the fall of an enormous volume of water from a great height, because of a variety of factors such as variation in the relative resistance of rocks, relative difference in topographic reliefs, fall in the sea level and related rejuvenation, earth movements etc. For example, Jog or Gersoppa falls on Sharavati (a tributary of Cauveri) has a fall of 260 metres.

A rapid, on the other hand, is a sudden change in gradient of a river and resultant fall of water (Fig.1.50).

3. Pot Holes:

The kettle-like small depressions in the rocky beds of the river valleys are called pot holes which are usually cylindrical in shape. Pot holes are generally formed in coarse-grained rocks such as sandstones and granites. Potholing or pothole-drilling is the mechanism through which the grinding tools (fragments of rocks, e.g. boulders and angular rock fragments) when caught in the water eddies or swirling water start dancing in a circular manner and grind and drill the rock beds of the valleys like a drilling machine. They thus form small holes which are gradually enlarged by the repetition of the said mechanism. The potholes go on increasing in both diameter and depth. (Fig. 1.51)

4. Terraces:

Stepped benches along the river course in a flood plain are called terraces. Terraces represent the level of former valley floors and remnants of former (older) flood plains. (Fig. 1.52)

5. Gulleys/Rills:

Gulley is an incised water- worn channel, which is particularly common in semi-arid areas. It is formed when water from overland-flows down a slope, especially following heavy rainfall, is concentrated into rills, which merge and enlarge into a gulley. The ravines of Chambal Valley in Central India and the Chos of Hoshiarpur in Punjab are examples of gulleys. (Fig. 1.53)

6. Meanders:

A meander is defined as a pronounced curve or loop in the course of a river channel. The outer bend of the loop in a meander is characterised by intensive erosion and vertical cliffs and is called the cliff-slope side. This side has a concave slope. The inner side of the loop is characterised by deposition, a gentle convex slope, arid is called the slip-off side. Morphologically, the meanders may be wavy, horse-shoe type or ox-bow/ bracelet type.

7. Ox-Bow Lake:

Sometimes, because of intensive erosion action, the outer curve of a meander gets accentuated to such an extent that the inner ends of the loop come close enough to get disconnected from the main channel and exist as independent water bodies. These water bodies are converted into swamps in due course of time. In the Indo-Gangetic plains, southwards shifting of Ganga has left many ox-bow lakes to the north of the present course of the Ganga. (Fig. 1.54)

8. Peneplane (Or peneplain):

This refers to an undulating featureless plain punctuated with low- lying residual hills of resistant rocks. According to W.M. Davis, it is the end product of an erosional cycle.

Depositional Landforms:

The depositional action of a stream is influenced by stream velocity and the volume of river load. The decrease in stream velocity reduces the transporting power of the streams which are forced to leave additional load to settle down. Increase in river load is effected through (i) accelerated rate of erosion in the source catchment areas consequent upon deforestation and hence increase in the sediment load in the downstream sections of the rivers; (ii) supply of glacio-fluvial materials; (iii) supply of additional sediment load by tributary streams; (iv) gradual increase in the sediment load of the streams due to rill and gully erosion.

Various landforms resulting from fluvial deposition are as follows:

1. Alluvial Fans and Cones:

When a stream leaves the mountains and comes down to the plains, its velocity decreases due to a lower gradient. As a result, it sheds a lot of material, which it had been carrying from the mountains, at the foothills. This deposited material acquires a conical shape and appears as a series of continuous fans. These are called alluvial fans. Such fans appear throughout the Himalayan foothills in the north Indian plains. (Fig. 1.55)

2. Natural Levees:

These are narrow ridges of low height on both sides of a river, formed due to deposition action of the stream, appearing as natural embankments. These act as a natural protection against floods but a breach in a levee causes sudden floods in adjoining areas, as it happens in the case of the Hwang Ho river of China. (Fig. 1.56)

3. Delta:

A delta is a tract of alluvium usually fan-shaped, at the mouth of a river where it deposits more material than can be carried away. The river gets divided into two or more channels (distributaries) which may further divide and rejoin to form a network of channels.

A delta is formed by a combination of two processes:

(i) Sediment is deposited when the load-bearing capacity of a river is reduced as a result of the check to its speed as it enters a sea or lake, and

(ii) At the same time fine clay particles carried in suspension in the river coagulate in the presence of salt water and are deposited. The finest particles are carried farthest to accumulate as bottom-set beds; coarser material is deposited in a series of steeply sloping wedges forming the forest beds; and the coarsest material is deposited on the braided surface of the delta as topset beds. (Fig. 1.57)

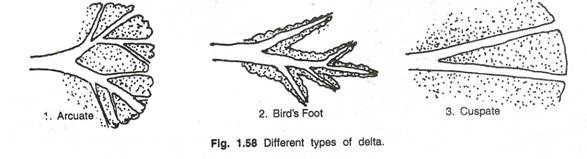

Depending on the conditions under which they are formed, deltas can be of many types.

1. Arcuate or Fan-shaped:

This type of delta results when light depositions give rise to shallow, shifting distributaries and a general fan-shaped profile. Examples: Nile, Ganga, Indus.

2. Bird’s Foot Delta:

This type of delta emerges when limestone sediment deposits do not allow downward seepage of water. The distributaries seem to be flowing over projections of these deposits which appear as a bird’s foot. The currents and tides are weak in such areas and the number of distributaries lesser as compared to an arcuate delta. Example: Mississippi river.

3. Estuaries:

Sometimes the mouth of the river appears to be submerged. This may be due to a drowned valley because of a rise in sea level. Here fresh water and the saline water get mixed. When the river starts ‘filling its mouth’ with sediments, mud bars, marshes and plains seem to be developing in it. These are ideal sites for fisheries, ports and industries because estuaries provide access to deep water, especially if protected from currents and tides. Example: Hudson.

4. Cuspate Delta:

This is a pointed delta formed generally along strong coasts and is subjected to strong wave action. There are very few or no distributaries in a cuspate delta. It has curved sides because of an even deposition of material on either side of the mouth.

Example:

Tiber river on west coast of Italy. (Fig. 1.58)

Fluvial Cycle of Erosion:

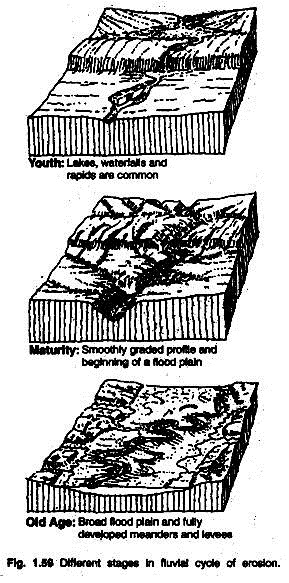

Three distinct stages of youth, maturity and old age can be identified during the lifetime of a stream.

Youth:

A few consequent streams exist and a few subsequent streams are trying to develop valleys by random headward erosion. These valleys may be “V shaped. The depth of these valleys depends on the height above sea level. The inter- stream divides are broad, extensive, irregular and may have lakes. Rapids, water-falls, gorges, river capture are characteristic features. Floodplain is generally absent, but may exist along the trunk stream. Overall, a highly uneven relief exists.

Maturity:

This stage is marked by well- integrated drainage system with a few streams trying to adjust through softer beds. Broad valleys result from continuous horizontal erosion. Meanders are a characteristic feature and valley floor width is more than the meander belt width. The inter-stream divides are sharp and the upland is reduced. Rapids and waterfalls are absent.

Floodplain development is a prominent feature. Maximum relief exists overall.

Old Age:

The streams are more numerous than in youth but less as compared to maturity. With increasing deposition valley broadening dominates. Meanders are highly developed with ox-bow lakes, and floor width is more than the meander belt width. The inter-stream divides are highly reduced. Lakes and marshes may be present. The successive floodplains join to form a pen plain. Delta formation is characteristic of old age at the mouth of the river. Mass wasting is dominant and, overall, minimum relief is evident. (Fig. 1.59)