ADVERTISEMENTS:

In this article we will discuss about the proof of land elevation and submergence with some accompanying phenomena.

Sea Beaches:

Two very characteristic results of sea- action are beaches and cliffs with caves in them. There are some beaches whose forms are modified by every high tide. Parts of them, again, are only touched by the spring tides, which are the highest tides of all, or when the sea is blown upon by gales from certain quarters. When such gales occur at the same time as a spring tide the sea may come abnormally far inland and wash up large quantities of beach material.

In this way what is called a Storm-beach may get formed. But there is a limit beyond which such storm-beaches are never driven. Yet at some parts of our coasts there is clear evidence of a beach far higher than the highest storm- beach, and not only so, but there are such beaches at different levels; they are called raised beaches.

Raised Beaches:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In some cases they abut against a line of cliff at some considerable distance from the present shore-line, and this cliff may have in it numerous caves (Fig- 3).

This is very well seen on the Ayrshire coast, where there is a beach 25 feet above the present sea-level, and a line of cliff behind it with numerous caves, the cliffs now being covered with grass and the mouths of the caves full of ferns.

Not only is there a line of beaches at the 25-foot level, but there is another at the 50-foot level, and still another at the 100-foot level.

Raised beaches are not so conspicuous or so well preserved along the coasts of England and Wales as they are in Scotland. But remains of them are to be seen, especially on our southern coasts (Fig. 4). In Ireland there are the remains of a sea-beach, above the present accumulation, which can be traced for 130 miles from Carnsore Point to Baltimore.

The level at which these old beaches are now found is not so high as it originally was, for we have good evidence of a more recent subsidence, which carried them down to a relatively lower level. Indeed the latest movement of which we have evidence along our coasts is one of submergence.

Whenever any excavation is made round our coasts, either for a dock or for the foundation of a pier, or for any other reason, we gain an insight into the Alluvial Deposits, as the beds of sand and mud laid down by rivers are called, which have recently been formed at those places.

Submerged Forests:

We continually find in such spots what are called submerged forests. Frequently the roots are found of oak trees which, at the time of their growth, must have been beyond the reach of the sea, for they cannot live in salt-water. Such vegetation occurs chiefly in the neighbourhood of river-mouths, and is especially well seen near the Mersey, where the peat full of roots of trees, in the position of growth, is beautifully exposed.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

During excavations for the Barry Dock at Swansea and at Southampton stone implements and bone needles, all made by man, were found on some of these depressed land-surfaces, and showed that submergence had gone on since man came to this country. The greatest depth to which these land-surfaces are now submerged is about 60 feet below the present river-levels.

According to Mr. Clement Reid, the south coast of England was, prior to this period of submergence, utterly unlike what we now see. Instead of bold cliffs there was a wide coastal plain extending out approximately to the present Io-fathom line. On the landward side of this belt was a steep grassy slope, the position of an old line of cliff. About 4000 years ago submergence of the land set in, a great part of the coastal plain was flooded, and the old cliff- line behind was once more brought within striking distance of the waves. At the same time the lower parts of our valleys were drowned and were often turned into sea-lochs which penetrated far inland.

This submergence may, according to Mr. Reid, have taken about 500 years to complete, and not till then did the coast-erosion we now see begin and our existing sea- beaches and sand-dunes commence to form.

In Scotland the evidence goes to show that the latest movement was an upward one. The sea-lochs, which penetrate far inland, represent the drowned ends of river- valleys, and as they occur almost entirely on the west coast they suggest that the submergence of the west was to a far greater depth than that of the east coast.

But the Scotch raised-beaches prove an uplift, and the 25-foot beach is proved to have been upraised after the arrival of early man in the country.

There seems no conclusive evidence that any part of our islands has either risen or sunk in historic times. But when we cross the North Sea there is clear proof that the north of Norway is rising and the south of the same country is falling at the rate of about a foot a century. And when we pursue our investigations into the older rocks we find abundant proof that the earth’s surface is not stationary, but that rocks, which were laid down under the sea, have been raised up and that terrestrial life now goes on over the spots where marine life once flourished.

The question naturally presents itself to our minds, how long will our islands remain in their present stationary condition? As will be shown in a succeeding chapter, marine and terrestrial conditions have continually alternated in times gone by, and there is everything to make us believe that at some future time our country will once more descend below the sea-level. But to the question about the length of time for which we may expect to remain above the sea, geology returns no answer.

Results of Submergence:

The probable results of an uprise and of a submergence of the land surface on its geography are worth discussing.

If a country has a system of rivers issuing from a hilly district and flowing over a fairly flat plain to the sea, then this plain will tend to remain as a shallow area if it sinks below sea-level.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This was no doubt what occurred in the area which is now the North Sea. The English east-coast rivers from the Humber to the Thames drained in former times farther to the east than they do now, and some of them were tributaries of a Rhine which flowed much farther to the north than does the Rhine of to-day.

At that time the more easterly rivers of Germany must have united to form a large estuary to the west of Denmark, and a watershed in the neighbourhood of the English Channel divided the streams which flowed eastwards into the Rhine from those which flowed westwards over a land which existed where the English Channel is now.

When submergence took place the waters of the North Sea crept southwards and severed the English rivers from the Rhine, and passing up the estuaries of the eastern German rivers separated them from one another.

But the shallow part of the North Sea between South- East England and Denmark remains as evidence of the former seaward extension of Germany and England. To the east of Yorkshire is the well-known shoal of the Dogger Bank, and from this bank the trawlers have for many years dredged large bones of land animals and loose masses of peat.

The kinds of animals which have been brought up from the Dogger Bank are the bear, wolf, hyena, Irish elk, reindeer, red-deer, wild ox, bison, rhinoceros, mammoth, beaver, and walrus. The masses of peat were found to consist exclusively of swamp vegetation, the only trees being birch, sallow, and hazel.

At a depth of about 60 feet, therefore, we find here the remains of an old land-surface, no doubt at one time continuous with the buried land-surface shown by borings in the east of England and at Amsterdam; submergence has produced a shallow sea, the scouring of whose waters has not been sufficient to remove yet the traces of the old land conditions.

Where, however, the sea-coast before submergence contained deep river-valleys, as in mountainous districts, there, after submergence, we should get long inlets of the sea, and the later rivers would be merely the heads of the old streams. Such occurrences are well known in the west of Scotland, and are called Sea-lochs.

Such a submergence as has been considered is one where a general depression of the surface goes on with no marked alterations in the relative levels of its various parts. Thus a whole tract of country may be lowered for 60 feet, but two points which are 100 feet vertically from one another still remain 100 feet apart.

Earth-Crumpling:

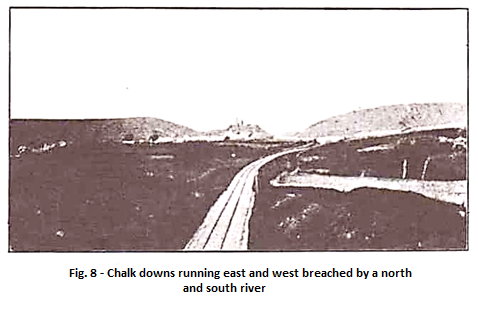

But there have been times when the surface, either above or below the sea-level of the time, has, been pressed sideways so that it has been bent into a series of arches and troughs; and if the crest of an arch were pushed above sea-level there would be a new fresh surface over which rivers would run. Such an earth-fold occurred long ago where the Weald country of Kent, Surrey, and Sussex is now.

The sea-floor was of soft beds lying on chalk, and when pushed up extended as mighty arch from the North to the South Downs. The streams running southwards and northwards over this fold ate their way into the rising arch and began to carve out their valleys in it. Side streams ran into the main rivers and general denudation went on.

River-Valleys:

Now a system of river-valleys is seldom, if ever, a stable one, owing to the fact that a stream not only works downwards, but backwards, and so captures water which at one time flowed down another river-valley. This working backwards of a river is not easy to understand, but may be made clearer by the following considerations.

Supposed that two streams are running along the paths AB and CD, but their gradients are different.

If AB has the steeper fall, it will, if other things are the same, cut its way down at a quicker rate than CD, and as the material at A is removed, the groove or valley in which AB was gets lengthened, so that the top of the valley is now at A’, while DC has only cut its way back to C’.

In the time the original stream AB may cut its way back into the valley of CD, and as its fall is the steeper the upper part of C’D will run down the valley of AB and thus C’D will be beheaded, its top waters being tapped off. The arrangement will then be—

As the new stream C’B, and KD, the remainder of C’D, cut down there will tend to be a nick left above K, which is an old valley floor over which CD originally ran.

Or further developments may occur:

The old top of the stream PQ may be captured by RS, and in the course of time a stream a may run down from the watershed T, so that α is now running in the opposite direction to the original stream PQ, which used to flow above the level of α.

Such a stream as α is called an Obsequent Stream.

Dry valleys frequently occur in our country which are due to the capturing by another stream of the head waters of the river which used to flow through them.

As has been noted, the chalk and the beds of rock above it in the south-east of England were at one time raised into a great arch, and rivers flowed off to the north to join the Thames and to the south to join a river which flowed down the English Channel. These rivers gradually cleared away the softer beds above and then cut down into the chalk.

There came a time when they cut through the chalk itself at the top of the arch and then they went on flowing north and south through the deep valleys which they had previously made through the chalk hills. As a consequence of this action we have such a stream as the Mole running straight at the North Downs near Dorking and, instead of turning aside when it meets the lofty chalk range and running along its base, it continues straight on through a valley which cuts right through the Downs.

The Medway, to the north of Maidstone, the Darent, north of Sevenoaks and the Wey, near Guildford, all behave like the Mole, coming up to the North Downs and cutting clean through them. On the other side of the arch the Arun, near Arundel, the Adur, north of Shoreham, the Cuckmere, near Seaford, and the Ouse, near Lewes, all run from the north up to the South Downs and pass through deep north and south valleys to the sea.

There are other places in England where similar gorges are to be seen, probably the most famous one being the Avon gorge, near Bristol. Here the Avon, running over fairly flat low country, runs up to the ridge of hard carboniferous limestone on which Clifton is built. Instead of turning along the base of this ridge, it enters a deep cleft in the hard rock, the almost vertical sides of which rise to a height of some 200 feet above the river.

All these gorges are evidences of a very different earth- surface which existed in past times. They bear witness to the great cutting power of a river and to a period when the land above the low country, through which the river now passes before it enters its gorge, must have risen to a higher level than the present top of the gorge.

We must therefore bear in mind not only that the edges of the land are being altered by denudation due to the sea, but that the surface of the land is being continually altered by running water.

The ridging up of the rocks into arches and troughs has been mentioned as an effect of pressure exerted more or less horizontally, but there are other effects of such compression which are possible.

If the beds are of such a nature that they will not stand much bending they snap, and then a definite movement of the rocks on one side of the crack takes place relatively to those on the other side.

Faulting:

Such a crack accompanied by a shifting of the beds is called a Fault, and sometimes the beds on one side are displaced for thousands of feet. We need not suppose, however, that, all this displacement occurs at one time, but rather that it has gone on little by little through vast ages.

Faults with small vertical movements are very common indeed. Considering how often the sea-floor in our regions has been raised and lowered it would be a surprising thing to find the beds unbroken. But there are some with a very big vertical movement which have very important results.

The Scotch Highlands and Southern Uplands are formed of hard rocks, none of them younger than the Silurian period, and between them, stretching from the mouths of the Tay and Forth on the east coast to the Firth of Clyde on the west, is a broad lowland consisting of Old Red Sand-stone and Carboniferous rocks which are of post-Silurian age.

This wide strip of lowland is separated from the Highlands to the north by one great fault, and from the Uplands to the south by another. It has, in fact, been preserved from denudation by having been let down to such a low level, the similar rocks which in former times lay over much country to the north and to the south of these faults having been entirely removed and the older rocks laid bare.

Another gigantic fault runs along the east side of the Malverns in the west of England. Here the newer beds to the east of the fault have been let down, and all traces of them on the older rocks to the west have been removed.

But besides the actual movement that beds of rock have undergone when pressure has been exerted on them there is an important change that has often greatly affected them.

Metamorphism:

When one uses a hand-pump to inflate a tyre one realises that compression produces a heating effect. In the case of the small pressures used in the case of such a pump the rise of temperature is never very great, but in the cases of the enormous pressures which may act on a rock deep down in the earth’s surface such a rise of temperature may occur that the minerals which make up the rock may be changed and new minerals crystallise out.

Such a change is called Metamorphism, and the resulting rock a Metamorphic Rock.

As the original unchanged rocks may differ widely from one another, so when metamorphosed they will also differ widely. A sandstone is often almost entirely made up of one material, quartz, and a clay is made up of many materials, while a limestone is largely made up of calcium carbonate.

When such rocks are heated, either by the injection amongst them of a large mass of molten rock or by pressure, the mineral changes produce very different metamorphic rocks.

In certain parts of our islands large tracts of the present surface are made up of very old metamorphic rocks called Gneisses or Crystalline Schists. Such tracts occur in the Scotch Highlands and in the north-west of Ireland. Smaller stretches of country formed of similar rocks are found in Anglesea, Carnarvonshire, the Malvern Hills, and the Lizard.

But the pressure to which a rock was subjected was not always so intense that any great mineral change went on.

A mud by pressure is first hardened to a mud-stone, and if the pressure is considerable there may be developed in the rock crystals of a mineral called Mica. Now, these crystals are very thin and flat, and when a layer of them is formed in a rock it forms a plane along which the rock will readily split.

When these layers lie along the original planes of deposition of the rock material the resulting rock is called a Shale; when the two planes cross one another it is called a Slate.

Some of our older muds have been changed by pressure into slates, and the most noted localities for hard slates used for roofing purposes are in North Wales and in the Lake District.