ADVERTISEMENTS:

Our earth is undergoing deformations imperceptibly but inexorably.

These deformations are caused by the movements generated by various factors which are not completely understood and include the following:

1. The heat generated by the radioactive elements in earth’s interior.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

2. Movement of the crustal plates due to tectogenesis.

3. Forces generated by rotation of the earth.

4. Climatic factors

5. Isostacy—according to this concepts, blocks of the earth’s crust, because of variations in density would rise to different levels and appear on the surface as mountains, plateaux, plains or ocean basins (See box for details).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Classification of Earth Movements:

Endogenetic Movements:

The interaction of matter and temperature generates these forces or movements inside the earth’s crust. The earth movements are mainly of two types: diastrophism and the sudden movements.

1. Diastrophism:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It is the general term applied to slow bending, folding, warping and fracturing.

Such forces may be further divided as follows:

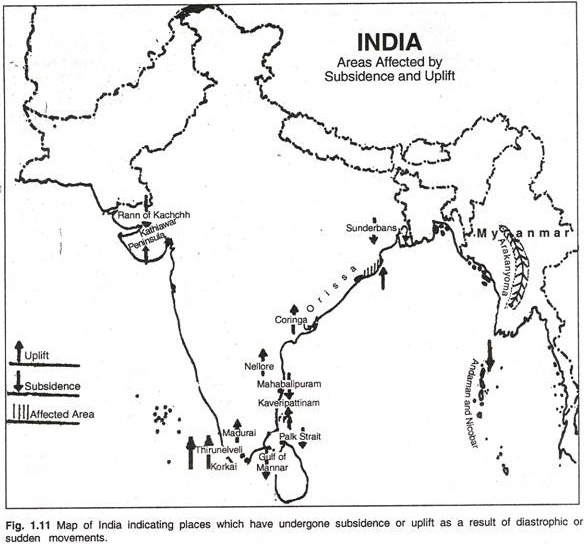

(i) Epeirogenic or continent forming movements act along the radius of the earth; therefore, they are also called radial movements. Their direction may be towards (subsidence) or away (uplift) from the centre. The results of such movements may be clearly defined in the relief.

Raised beaches, elevated wave-cut terraces, sea caves and fossiliferous beds above sea level are evidences of uplift. One of the reasons for believing that the Deccan was uplifted is that the nummulitic limestones rest uncomfortably on the basaltic lavas near Surat well above sea level.

Raised beaches, some of them elevated as much as 15 m to 30 m above the present sea level, occur at several places along the Kathiawar, Orissa, Nellore, Madras, Madurai and Thirunelveli coasts. Several places which were on the sea some centuries ago are now a few miles inland. For example, Coringa near the mouth of the Godavari, Kaveripattinam in the Kaveri delta and Korkai on the coast of Thirunelveli, were all flourishing sea ports about 1,000 to 2,000 years ago.

Evidence of marine fossils above sea level in parts of Britain and Norway is another example of Epeirogenic uplift.

Submerged forests and valleys as well as buildings are evidences of subsidence. In 1819, a part of the Rann of Kachchh was submerged as a result of an earthquake. Presence of peat and lignite beds below the sea level in Thirunelveli and the Sunderbans is an example of subsidence. The Andamans and Nicobars have been isolated from the Arakan coast by submergence of the intervening land. On the east side of Bombay Island, trees have been found embedded in mud about 4 m below low water mark.

A similar submerged forest has also been noticed on the Thirunelveli coast in Tamil Nadu. A large part of the Gulf of Mannar and Palk Strait is very shallow and has been submerged in geologically recent times. A part of the former town of Mahabalipuram near Chennai (Madras) is submerged in the sea. (Fig. 1.11)

(ii) Orogenic:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Orogenic or the mountain-forming movements act tangentially to the earth surface, as in plate tectonics. Tensions produces fissures (since this type of force acts away from a point in two directions) and compression produces folds (because this type of force acts towards a point from two or more directions). In the landforms so produced, the structurally identifiable units are difficult to recognise.

In general, diastrophic forces which have uplifted lands have predominated over forces which have lowered them. (For diagrams showing effects of Diastrophic Movement, see Figures 1.12, 1.13. 1.14. 1.15, 1.16)

2. Sudden Movements:

These movements cause considerable deformation over a short spans of time, and may be of two types:

(i) Earthquake:

It occurs when the surplus accumulated stress in rocks in the earth’s interior is relieved through the weak zones over the earth’s surface in form of kinetic energy of wave motion causing vibrations (at times devastating) on the earth’s surface. Such movements may result in uplift in coastal areas.

Another earthquake in Chile (1822) caused a one-metre uplift in coastal areas. Another earthquake in New Zealand (1885) caused an uplift of upto 3 metres in some areas while some areas in Japan (1891) subsided by 6 metres after an earthquake.

Earthquakes may cause change in contours, change in river courses, ‘tsunamis’ (seismic waves created in sea by an earthquake, as they are called in Japan) which may cause shoreline changes, spectacular glacial surges (as in Alaska), landslides, soil creeps, mass wasting etc. (Fig. 1.17)

(ii) Volcanoes a volcano is formed when the molten magma in the earth’s interior escapes through the crust by vents and fissures in the crust, accompanied by steam, gases (hydrogen sulphide, sulphur dioxide, hydrogen chloride, carbon dioxide etc.) and pyroclastic material. Depending on chemical composition and viscosity of the lava, a volcano may take various forms. (Fig. 1.18)

(a) Conical or Central Type:

When cooled lava particles from successive volcanic eruptions form a cone around the vent, a conical mountain shape emerges. This is a central type of volcano. Examples: Fujiyama (Japan) and Mount Vesuvius (Italy). The magma in such volcanoes is viscous, acidic and silicate.

(b) Shield Type:

The less viscous, less acidic and less silicate magma flows out slowly and quietly and gives rise to a wide-based plateau like formation with a gentle slope. Thus, a ‘shield shaped’ volcano with thin horizontal sheets emerges. Example: Mauna Loa (Hawaii).

(c) Fissure Type:

Sometimes, a very thin magma escapes through cracks and fissures in the earth’s surface and flows after intervals for a long time, spreading over a vast area, finally producing a layered, undulating, flat surface. Example: Deccan traps (peninsular India)

(d) Caldera Lake:

After the eruption of magma has ceased, the crater frequently turns into a lake at a later time. This lake is called a ‘caldera’. Examples: Lonar in Maharashtra and Krakatao in Indonesia.

Volcanic Landforms:

The intrusive activity of volcanoes gives rise to various forms. (Fig. 1.19)

Batholiths:

These are large rock masses formed due to cooling down and solidification of hot magma inside the earth. Batholiths form the core of huge mountains and may be exposed on surface after erosion.

Laccoliths:

These are basically intrusive counterparts of an exposed domelike batholith.

Dykes:

These are solidified vertical lava layers inside the earth.

Sills:

These are solidified horizontal lava layers inside the earth.

Other features created by volcanoes include hot water springs, geysers etc.

Exogenetic Forces—Weathering and Erosion:

These forces act over the earth’s surface and basically involve the process of ‘gradation’, which in turn is achieved by the simultaneous process of ‘degradation’ and ‘aggradation’. The exogenetic forces involve two stages—firstly; the landforms (in form of rocks) weaken, break up, rot and disintegrate. This stage comes into play as soon as the newly created landform is exposed to the influence of weather. This stage is called Weathering.

Then comes a stage of scraping, scratching and grinding on the surface rock. It includes removal or transportation of the weathered rock material from one place to another. This stage is called Erosion. The act of erosion is performed by a number of natural agents, such as running water, ground water, moving ice, wind, waves and currents of the sea. These agents use the eroded material as cutting tools to carve out and shape the landscape.

Erosion is a mobile process while weathering is a static process because the disintegrated material and the products (or the result of weathering) do not involve any motion except the falling down of the material by the force of gravity.

The reverse process of filling up of depressions on the earth’s surface by the material deposited by the same agents of erosion is called aggradation or deposition. Weathering may be physical, chemical or biological depending on the nature of agents and the processes involved and the products created.

1. Physical Weathering:

The disintegration of rocks by mechanical forces is called physical or mechanical weathering. This type of mechanical force produces fine particles from massive rock by the exertion of stresses sufficient to fracture the rock, but does not change its chemical composition. Physical weathering may take place in many ways.

These are discussed below:

(i) Granular Disintegration:

Rocks composed of coarse mineral grains commonly fall apart grain by grain or undergo granular disintegration.

(ii) Exfoliation:

A rock mass disintegrates layer by layer leaving behind successively smaller spheroidal bodies and forming curved rock shells by disintegration. This type of rock break-up is also called spalling. These layers separate due to successive cooling and heating with changes in temperature.

(iii) Block Separation:

This type of disintegration takes place in rocks with numerous joints acquired by mountain-making pressures or by shrinkage due to cooling. This type of disintegration in rocks can be achieved by comparatively weaker forces.

(iv) Shattering:

A huge rock may undergo disintegration along weak zones to produce highly angular pieces with sharp corners and edges through the process of shattering. (Fig. 1.20)

(v) Frost Action:

This type of weathering is common in cold climates. During the warm season, the water penetrates the pore spaces or fractures in rocks. During the cold season, the water freezes into ice and its volume expands as a result. This exerts tremendous pressure on rock walls to tear apart even where the rocks are massive.

(vi) Mass Wasting:

Since gravity exerts its

force on all matter, both bedrock and the products of weathering tend to slide, roll, flow or creep down all slopes in different types of earth and rock movements grouped under the term ‘mass wasting”.

This may take place in a variety of ways:

(a) Talus Cones Rock:

Particles created by processes of mechanical weathering move down high mountain slopes and steep rock walls of gorges. These particles tend to get deposited in a distinctive landform, the talus cone. A talus slope or scree slope has a constant slope angle of 34o or 35o.

(b) Earth flow:

In humid climate regions where there are steep slopes, the masses of soil saturated with water, overburden or weak bedrock may slide downslope during a period of a few hours in the form of earth flow.

(c) Landslide:

This is rapid sliding along hill slopes of rock mass. It may take place either by rockslide along a relatively flat inclined rock plane or by slump mechanism involving a rotating motion of the sliding rockmass on a slightly curved slope,

(d) Soil Creep:

This is extremely slow downslope movement of soil and overburden on almost all moderately steep, soil-covered slopes. Soil creep occurs as a result of some disturbance of the soil and mantle caused by heating and cooling of the soil, growth of frost needles (by frosting process), alternate drying and wetting of the soil, trampling and burrowing by animals and shaking by earthquakes. Because gravity exerts a downhill pull on every such rearrangement, the particles are urged progressively downslope. Rock fragments of larger size may accumulate at the mountain base to produce a boulder field.

(e) Mudflow:

In regions with sparse vegetation to check the flow of water, the sudden flow of water due to rain acquires a muddy character on its journey downslope. As it follows the stream course, it gets thicker and thicker until it becomes so overburdened as to come to a stop. It may carry huge boulders on its way. Such mudflows may cause massive loss of life and property.

(f) Solifluction:

This form of mass wasting is common in the Arctic regions. In late spring and early summer, the water penetrates and saturates the upper few feet of the soil, but is unable to go deeper because of frozen conditions below. The upper saturated soil mass starts flowing along slopes. This movement causes the formation of terraces and lobes due to punctuated deposition.

2. Chemical Weathering:

This causes rocks to decay i.e. to decompose instead of disintegrating.

The mineral contained in the structure of rocks undergo chemical changes when they get in contact with atmospheric water and air. These chemical changes cause rock particles to break up due to decomposition. Atmospheric water contains oxygen, carbon, sulphur, hydrogen etc. and the air also contains oxygen, nitrogen, carbon dioxide. High levels of temperature and water content enhance the pace of chemical reactions.

The chemical reactions may be classified as follows:

(i) Carbonation:

It takes place in rocks containing calcium, sodium, magnesium, potassium etc. when they come in touch with rain water which contains dissolved carbon dioxide. This process is common in lower humid climates.

(ii) Chlorination:

It takes place when chloride salts are formed as a result of chemical reaction.

(iii) Oxidation:

This occurs in iron-based salts. The atmospheric oxygen present in rainwater unites with mineral grains in the rock, especially with iron compounds. This results in the decomposition of the rock and it starts crumbling. This process is called oxidation and is similar to the process of rusting.

(iv) Hydration:

The chemical action of water detaches the outer shell of aluminium-bearing rocks through the process of hydration.

(v) Desilication:

Removal of silica from rocks also leads to their weakening and eventual disintegration due to desilication.

(vi) Solution:

Some minerals, such as rock- salt and gypsum, are removed by the process of solution in water.

The chemical reaction of rainwater brings about decomposition of minerals more rapidly than its mechanical action. The chemical weathering is capable of breaking up even a hard crystalline rock into minute particles.

3. Biological Weathering:

This refers to disintegration, break-up and decomposition of rock masses by plants, animals and activities of man.

Plant roots penetrate the cracks in rocks or at the rock base and dislodge large blocks from the cliffs. Roots may also cause breakup of the rock. The burrowing by earthworms, ants, rats and the like makes channels through the rock and contribute to their destruction.

The excretions of many of these animals provide acids that bring about a gradual decay of the rock. Many activities of man, such as mining, quarrying, deforestation and unscientific agricultural practices (like shifting cultivation) etc., add to the weathering of rocks. Biological weathering may be physical or chemical in nature.

Effects of Weathering:

Weathering and erosion tend to level down the irregularities of landforms and create a peneplane. Weathering may cause visibly identifiable changes in the’ general landscape. A general darkening of rocks, especially in dry climates due to chemical action, creates desert varnish and patination which basically involves changes in rock skin without change in the volume. The strong wind erosion leaves behind whale-back shaped rocks in arid landscape.

These are called inselberg or ruware. Sometimes a solid layer of chemical residue covers a soft rock, through a process known as rind or case hardening. The hollowing action of weathering produces weathering pans or pits, which are also known as gramma or taffoni. Sometimes, differential weathering of soft strata exposes the domelike hard rock masses, called tors. Tors are a common feature of South Indian landscape.