ADVERTISEMENTS:

In this article we will discuss about:- 1. Location of Tundra Biome 2. Climate of Tundra Biome 3. Vegetation Community 4. Animal Community 5. Man and Tundra Biome.

Location of Tundra Biome:

Tundra is a Finnish word which means barren land. Thus, tundra region having least vegetation and polar or arctic climate is found in North America and Eurasia between the southern limit of the permanent ice caps in the north and the northern limit of temperate coniferous forest of taiga climate in the south.

Thus, tundra biome includes parts of Alaska, extreme northern parts of Canada, the coastal strip of Greenland, and the arctic seaboard regions of European Russia and northern Siberia. Besides, tundra biome has also developed over arctic islands. Vegetations rapidly change to the north of tree line because of increasing severity of climate.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus, based on variations in the general characteristics of vegetations in the arctic tundra (tundra biome is divided in two sub-divisions e.g., arctic tundra biome and alpine tundra biome where the latter is found over high mountains of tropical to temperate areas).

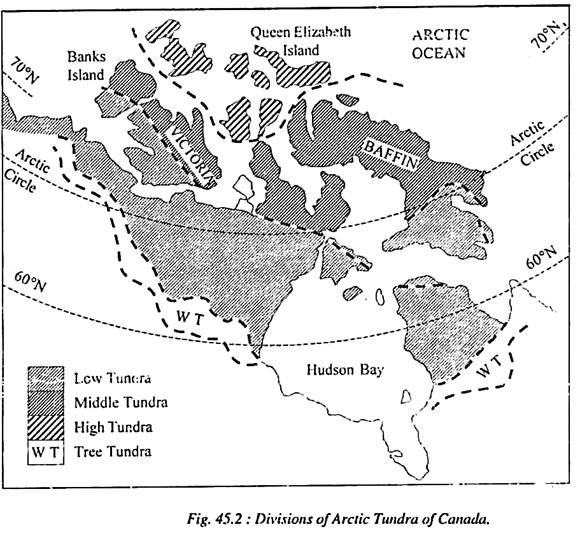

Three zones are recognized from south to north viz.:

(i) Low arctic tundra,

(ii) Middle arctic tundra, and

(iii) High arctic tundra.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It may be pointed out that high, middle and low are not indicative of altitudes rather these indicate latitudes.

Low arctic tundra is the southern most zone of arctic tundra which includes most of northern Canada, northern Alaska, southern parts of Canadian islands (e.g., southern parts of Banks, Victoria and southeastern part of Baffin islands), southern coastal lands of Greenland and Siberian Peninsula. High arctic tundra includes the islands located to the north of Canadian archipelago (e.g., Queen Elizabeth island groups).

This zone is characterized by sparse vegetations such as mosses, lichens and hardy herbs (such as avens and saxifrages). Middle arctic tundra is found between High Tundra in the north and Low Tundra in the south.

Climate of Tundra Biome:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The tundra or the polar climate is characterized by general absence of insolation and sunlight and very low temperature throughout the year. This severe climatic condition does not favour much vegetative growth and hence most of the tundra remains a barren land. There is total lack of trees. The ground surface is covered with snow at least for 7 to 8 months each year.

Temperature is generally below freezing point. The region is swept by speedy cold powdery storms known as blizzards. Growing season is less than 50 days in a year. The ground is permanently frozen (permafrost).

Even soil is also perennially frozen. Mean annual precipitation, mostly in the form of snowfall, is below 400mm. Winters are long and very severe whereas summers are short, moderately cool but pleasant.

Vegetation Community of Tundra Biome:

There is perfect relationship between vegetation and the condition of moisture in the soils. The characteristic lithosols of the tundra biome (a well-drained soil) support only lichens and mosses. Arctic gray soils favour the growth of dwarf herbaceous plants and bog soils maintain sedges and mosses.

Only 3 percent species of the total world species of plants could develop in the tundra biome because of the severity of cold and absence of minimum amount of insolation and sunlight. The vegetations of the tundra biome are cryophytes i.e., such vegetations are well adapted to severe cold conditions as they have developed such unique features which enable them to withstand extreme cold conditions.

According to N, Pollumin (1959) there are families of cryophytes in Arctic Tundra Biome. The number of plant species and plant population decreases northward with increasing severity of cold. Most of the plants are tufted in form and range in height between 5 cm and 8 cm.

These, plants have the tendency of sticking to the ground surface because the temperature of the ground surface is relatively higher than the temperature of the overlying air. The herbs are developed mainly in those areas where heaps of ice and snow protect the plants from gusty icy winds. Such herbaceous plants include willow (Salix herbacea and Salix arctica).

The stems and leaves of these herbaceous plants are very close to the ground surface (hardly a few centimetres above the ground surface). Though the growth rate of these herbaceous plants is exceedingly slow but their survival period is unbelievably very long (between 150 to 300 years).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The evergreen flowering plants develop on the ground like cushions mostly during short cool summers. These flowering herbaceous plants include moss campion (Silene acaulis). Some plants assume the shape of rosette where in the leaves radiate from a point and leafless stalk bearing flower grows upward. Saxifragus nivalis is the typical species of rosette plants. Some plants are endowed with the typical features of fleshy leaves, thick cuticle and external covers of hairs (epidermal hairs) around their stems and branches.

Some plants grow on the ground like tussocks while other groups of plants grow horizontally on the ground surface like mats or compact turf (such as Dryas octopetala). It may be pointed out that the period available for the growth of tundra plants is of only 50 days during cool summer season, during which all the stages of the life-cycle of a plant are completed e.g., growth of plant tissues, flowering, pollination, ripening of seeds, dispersal of seeds and establishment of seedlings etc.

Animal Community of Tundra Biome:

The animals of Arctic Tundra Biome are grouped into two categories viz.:

(i) Resident animals, and

(ii) Migrant animals.

Most of the animals leave Arctic Tundra and migrate southward during winter season to escape severe cold because only those animals stay at home during severe winter season which have such typical body structures which enable them to withstand the severity of cold.

Thus, the resident animals of relatively larger size have thick and dense insulating coat of fur or feathers around their bodies. Such epidermic insulating cover of fur or feathers works as blanket and keep the animals warm during severe winters. The American musk ox is a typical example of such animals. This bulky herbivorous animal living in the Arctic Tundra of Alaska, northern Canada and Greenland is endowed with epidemic coat of dense and soft wool around his body and an outer cover of thick and long hairs which are so long that they touch the ground.

This thick coat protects the musk ox from cold and moisture because this thick coat works as insulator and is impervious for both, cold and moisture. Musk ox gets rid off this heavy coat during summer season to adjust with relatively Warmer environment. Thus, after shedding thick hairy and wooly coat the musk ox presents a ragged appearance. The animal is again endowed with this coat during next winter.

The arctic fox has double coats of fur around its body and thus is able to withstand very severe cold. It may be pointed out that the fur coat of the arctic fox enables to hear as much low temperature as -50°C and hence the animal is active even during severe winter season and is able to catch its prey such as lemmings and hares. The resident birds have feathers (such as ptarmigan) which protect them from severe cold. In fact, these feathers work as insulators. The smaller birds protect them from severe cold by shivering or by fluffing their feathers.

Some resident animals of the Arctic Tundra Biome change their colour during different seasons of the year. For example, ptarmigan (a kind of bird) changes the colour of its feathers thrice a year. The arctic foxes and stoat, prominent predator animals having fur coat, are brown in colour during summer season but become white in colour during winter season.

Some animals such as wolves and caribou have such hairless feet which act as insulator and do not allow the heat of their bodies to escape. Some smaller animals such as rodents, lemmings, shrews, voles etc. live in burrows and tunnels during winter season to protect them from severe cold and hungry predator animals.

The second category of animals of the Arctic Tundra Biome consists of migratory animals which start migrating with the beginning of winter season to warmer areas in the south and return back to their native places during coming spring season. The animals move away from their native places during every winter season because they are not equipped with suitable devices which may enable them to protect themselves from the severity of cold as is the case with the resident animals as referred to above.

The birds, such as waterfowl, ducks, swans, geese etc., are the first to leave their native places with the arrival of autumn and are also first to come back to their original places in the spring or early summer. Some birds establish sexual contact before they return to their native places during summer season.

Some birds return to the same nests which they left at the time of their migration during winter season. Since the summer season is of very short duration and many functions and duties like nesting, pairing or courtship (sexual contact between the pair of male and female birds), laying of eggs, hatching and rearing of offsprings are to be completed within this short period, the most of the birds are not used to have sexual contacts for long duration.

Some birds cover very long distances during the period of their migration. For example, the arctic tern is the most important migratory bird, as it breeds during summer season in the Arctic Tundra and leaves its native place with the beginning of winter season and reaches as far south as Antarctica in the southern hemisphere which is characterized by summer season.

It is obvious that the arctic tern is benefitted from two summer seasons in a single year. Mosquitoes, midges and blacky are important species of insects which emerge in huge and dense swarms in pools, ponds, lakes, bogs and swamps during summer season. Tundra birds feed and rear their offsprings on huge populations of insects, molluscs and worms which also emerge in huge swarms during summer season in pools, ponds, rivers, lakes, swamps and soils.

Raindeer and caribou are important animals of the category of large migratory animals. These mammals spend winter season in temperate coniferous forest biome or taiga biome located to the south of their native tundra biome and establish sexual contact. It may be pointed out that the female raindeer and caribou conceive through winter mating (sexual intercourse between male and female animals) during their winter migration to temperate coniferous forest but they deliver their offsprings in tundra regions during summer season when they migrate from temperate coniferous forests to tundra biome.

Thus, raindeers and caribous cover distances of hundreds of kilometres each year between summer and winter seasons of the same year. Sometimes mother raindeer and caribou deliver young ones in the transit and such newly born youngones perish in the way because they are unable to undertake arduous long journey. These animals again move southward in herds as the arrival of winter season is heralded.

This annual rhythm of migration of animals from tundras to southerly temperate coniferous forest regions during winter season and from the latter to the former during summer season continues without any interruption. It is significant to note that this seasonal migration of tundra animals is motivated by the availability and non-availability of food which is itself created by varying weather conditions of the region.

The migrating herds of raindeer and caribou are attacked by wolves and several weak, lame and ill animals and many young ones are killed and eaten away by predators. These animals are also attacked by great swarms of numerous mosquitoes and many bloodsucking insects during their summer stay in tundra region. These animals have no better alternative to escape from the attack of aforesaid insects than to take temporary refuge in ponds, lakes or streams which ever is nearer to their localities.

Primary productivity in tundra biome is exceedingly low because of:

(i) Minimum sunlight and insolation,

(ii) Absence or scarcity of nutrients (such as nitrogen and phosphorous) in the soils,

(iii) Poorly developed soils,

(iv) Scarcity of moisture in the soils,

(v) Permanently frozen ground (permafrost), and

(vi) Very short growing period (about 50 days) etc.

According to V.D. Alexandrova (1970) the mean regional primary productivity decreases from low Arctic Tundra (228 dry grams per square metre per year) to high Arctic Tundra (142 dry grams per square metre per year) whereas the lowest primary productivity of 12 dry grams per square metre per year is found in the polar desert areas. The net primary productivity (NPP) of the Tundra Biome is 140 dry grams per square metre per year whereas the total net primary production of all parts of the tundra biome is 1.1 × 109 tons per year.

It may be pointed out that because of severity of climate and resultant poor vegetation, dry areas produce little litter but wet litter accumulates to form peat, and there is very slow and thus low nutrient release to vegetation. It is thus clear that the scarcity of food makes the tundra animals migratory.

Man and Tundra Biome:

Man is closely associated with the biota of the Tundra Biome because even his very existence depends upon animals of both terrestrial and aquatic habitats. About 50 years ago the Eskimos of Greenland, northern Canada and Alaska; Lapps of northern Finland and Scandinavia; Samoyeds of Siberia; Yakuts of Leena basin and Koryaks and Chuckchi of northeastern Asia spent complete nomadic life depending on their food derived from fish, seals, walruses, polar bears and other animals and on other commodities derived from caribou (the relative of Eurasian raindeer is called caribou in North American Tundra), raindeer and various fur animals.

Thus the earlier nomadic tundra man inflicted a great damage to tundra animals through his hunting activities. But now the situation has changed as many of the people of the Tundra Biome are leading a permanent or semi-nomadic life. The Eskimos have established permanent settlements and have formed villages in the coastal areas of tundra region and have domesticated caribou and fur animals. Many of Eskimo children have got modern education in the schools.

They have adapted to new technologies. For example, deadly rifles have replaced the traditional and out-dated harpoons. Thus, the modem Eskimos equipped with modern technologies are now in a position to damage the tundra ecosystem in the same way as is done by already technologically advanced man in other biomes.

The Samoyeds and other tribes of the Eurasian Tundra have also adapted new way of life. Some of them are leading permanently settled life. They rear raindeers and fur animals and even grow food crops mainly wheat in the Siberian Tundra while some tribes still wander with their herds of raindeer across the Eurasian Tundra in search of pastures.