ADVERTISEMENTS:

In the reconstruction of a region or a nation, transport systems invariably play a vital role. The growth and development of transportation provides a medium, contributing to the progress of agriculture, industry, commerce, administration, defence, education, health or any other community activity. Many of the regional characteristics that are influencing the layout of the existing transformational system are the creation of their antecedent transformational features.

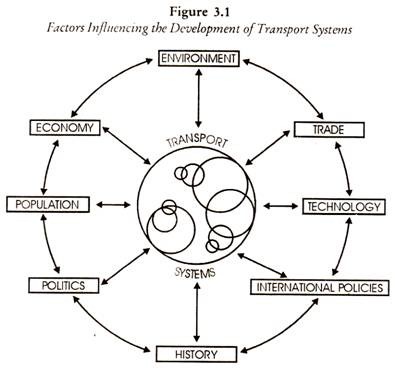

The present-day transport network has evolved out of the past framework because as trail evolves successfully into the pioneer dirt road, then into the improved farm road and finally, into the present day paved highways with heavy motor traffic. Many factors are involved in the development of a transport system. The present-day transport system of a country or a region cannot be explained by one factor alone. In fact, services of interrelated factors are responsible for the development of transport system as depicted in Figure 3.1.

White and Senior (1983), in their book entitled, Transport Geography considered five basic factors, which influence the growth and development of transport systems and the ways in which changes take place.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

These are:

1. The historical factor – this involves the location and pattern of systems, technological development, and institutional development and settlement, and land-use patterns.

2. The technological factor – the technological characteristics of each major transport mode are considered together with a discussion of the effects of technological advances.

3. The physical factor – this includes physiographic controls upon route selection, and geological and climatic influences.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

4. The economic factor – the structure and nature of transport costs are examined, together with service quality and methods of pricing and charging.

5. Political and social factors – these include political motives for transport facilities; government involvement in capital, monopolies and competition, safety, working conditions and coordination between modes; transport as and employer and the social consequences of transport developments.

The above mentioned factors affect transport in different ways, influencing each other as well as affecting transport systems directly and indirectly. Transport systems themselves, together with the physical environment within which they are set, also influence all these different areas of human activity. Each factor may operate in a positive, negative or neutral way; each may affect transport on different scales, from the local to the global; and two basic dimensions time and space are involved.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

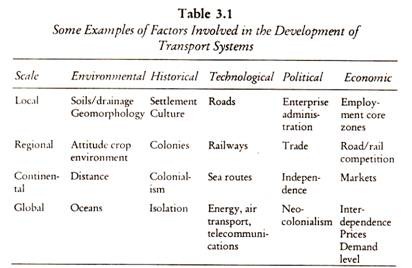

The following table indicates examples of some of these factors:

In considering the relative importance of factors affecting transport in a particular county or area, geographers not only use general models but also emphasise the diversity of place, and the specific combination of factors, which help to explain the development pattern of a transport system.

Models of Transport Development:

Several conceptual models have been devised as aids to the understanding of the development of transport systems and their counterparts in their approach. Ekstrom and Williamson (1971) recognise an initial phase, with the introduction of a new transport mode, followed by a spread phase with spatial diffusion of the network and a coordinating phase where the new and existing modes become integrated. These three may be followed by a concentration phase, involving an emphasis upon certain flows along selected routes. Finally, there is possibility that certain routes may decline or demise, termed as the liquidation phase.

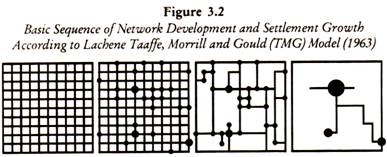

Lanchene Model (1965) has been developed to explain the development of transport system upon a hypothetical isotropic plain (Figure 3.2). It is just like Losch’s approach to the evolution of an economic landscape, progressing from an initial network of paths and trails arranged in a grid pattern to the selective growth of towns and villages and culminating in a smaller number of high-order settlements connected with high-grade routes such as railways and highways.

Taaffe, Morrill and Gould (TMG) Model (1963):

Taaffe, Morrill and Gould, in 1963, undertook a comparative analysis of the development of transport in developing countries and they were able to show that certain broad regularities permitted “a descriptive generalisation of an ideal typical sequence of transportation development”.

Their spatial model of transport network development in developing countries has proved to be a valuable help in the understanding of transport development and has been widely applied. The model which Taaffe and his colleagues devised was based upon Ghanaian and Nigerian experience, but it has been found to be applicable to other developing lands, for example, in Latin America.

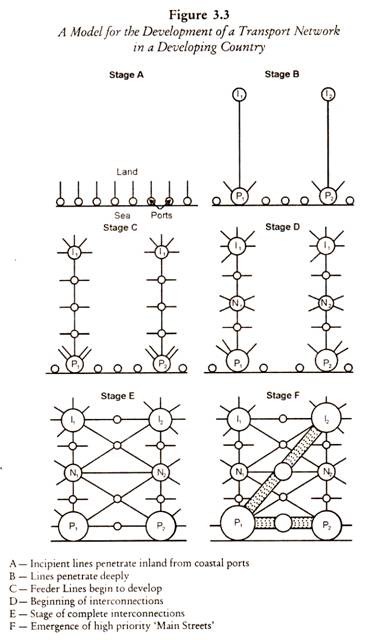

Taaffe et al. identified six stages in their sequence of transportation development. Figure 3.3 illustrates the sequential stages in the evolution of the transport network. The first stage consists of scattered settlements and small ports along a coast, which arose from colonial occupation. Such coastal settlements developed trading functions, though in the beginning these were of a very limited nature and, in consequence, their hinterlands were very restricted.

Furthermore, there was little lateral inter-connection between the scattered settlements, except for those effected by native fishing craft of occasional trading ships. The second stage evolved slowly but gradually as lines of inland penetration developed and some of these which linked up mining settlements or centres of population became more important than the others.

With the emergence of these major lines of penetration, often linked to the best located of the coastal ports, port concentration begins to develop and these commence to grow at the expense of their neighbours, some of which eventually disappear as trading centres or at best linger on as relict ports. This second stage goes on, hand in hand with the growth of an efficient administrative system and, more particularly, with the expansion of production for export.

The third stage is marked by the development of ‘feeder’ routes which focus more particularly upon the main ports and the more important centres in the interior. At the same time, as the growth in the export trade stimulates economic expansion generally in the hinterland, a number of intermediate centres begin to develop along the major access routes. In the fourth stage, these intermediate centres begin to develop into nodes which become focal points for feeder networks of their own.

The beginnings of lateral interconnection also takes place with lands between the major ports and the major inland towns being affected. Stage five sees the emergence of complete interconnections as the various feeder networks grow around the ports, major inland centres and main-line nodes and begin to link up.

Finally, in stage six, as the economy becomes more developed and integrated, all the principal centres and many of the minor centres are linked together in the transport system, while a number of high priority trunk routes develop which link the largest or most important centres.

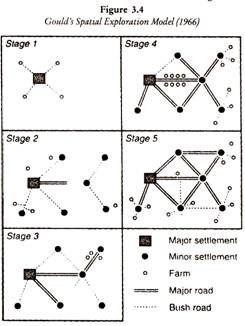

Aloba (1983) has applied the Taaffe, Morrill and Gould model to a rural area of West Africa as shown in Figure 3.4.

Gould’s Spatial Exploration Model (1966):

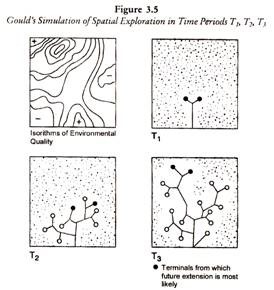

The behavioural model was proposed in 1966 as an alternative to the Taaffe, Morrill and Gould concepts of transport development. It incorporates a random approach and is based upon a simulation of search theory, with the development of a transport network within an area, which contains resources and hazards, or constraints, indicated by isorithms of environmental quality.

The developer aims to tap the resources of a previously unexploited area, depicted as a square, by building roads from a port on the coast, which forms one side of this square. As road building proceeds so the developer will encounter the resources and the constraints, such as mountains or rivers, within the environment. In stage one capital is invested in roads, which diverge from the port in straight lines.

In stage two, information on the nature of the resources or of the hazards encountered by the advancing roads is fed back to the development who may react in one of two ways. The resource already tapped may be exploited by investing in all-weather roads, or the search may be continued for other resources by extending the road network. Stage three comprises the construction of further links following the principles outlined in the first two stages (Figure 3.5).

The Vance Model (1970):

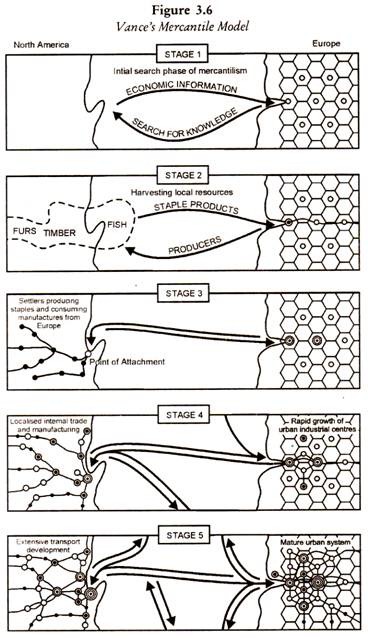

Based on his work on the eastern seaboard of America, Vance (1970) developed a five-stage ‘mercantile’ model to illustrate the development of transport links and the growth of the urban hierarchy in North America (Figure 3.6). Although primarily concerned with trade, his model is important in that it stresses the impact of exogenous forces on the evolution of transport networks and their associated spatial patterns.

In the initial stage, an accumulating of wealth in Europe prompted overseas expansion of an exploratory nature. Stage 2 sees the beginnings of the transatlantic trade routes based on the one-way trade in staple products such a fish, furs and timber. From 1620, permanent settlement occurs in North America; this results in Atlantic trade in both directions as settlers begin to produce commodities for export and consume manufactured products from a rapidly industrialising Europe (stage 3). Internal transport links are limited but all are externally orientated, a process that results in linear patterns both along the coast and stretching into the interior.

The 4th stage of the model is characterised by the development of internal trade and an internal manufacturing industry. The final stage of the model is reached when internal trade dominates North America and is matched by a mature transport and urban system in Europe. Although North America was eventually to lead the world in transport developments, the historical evolution is still apparent in both its transport network and its urban system.

The Rimmer Model (1977):

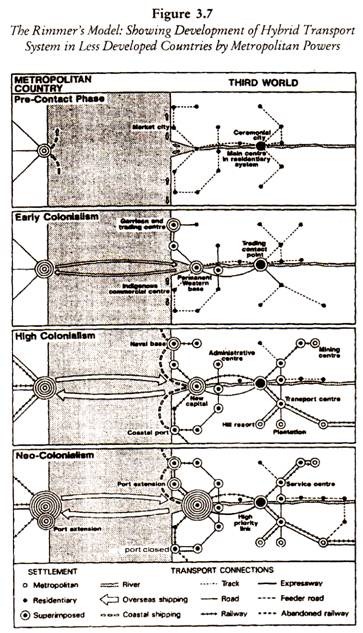

Using terminology derived from Brookfield (1972, 1975), Rimmer identified four phases in the evolving interrelationships between metropolitan and Third World countries in transport terms (Figure 3.7).

1. A pre-contact phase involved no links between a Third World country and a distant power in the advanced world. Within the Third World country, a limited network of tracks, together with navigable waterways, supported a relatively restricted socio-economic and political system.

2. An early colonial phase, secondly, involved the establishment of direct contacts by sea between advanced and developing countries but did not produce radical changes in Third World societies, Europeans being largely content to dominate sea transport routes and to establish foothold settlements such as trading posts and garrisons.

3. A third phase of high colonialism involved more fundamental changes including the introduction of roads and railways, port facilities and inland transport nodes, and the diversification of economic activity (including industrialisation and commercial agriculture) and settlement patterns (including rapid urbanisation).

4. A fourth neo-colonial phase involves a substantial further diversification of the economic development surface of the Third World country and continuing (if modified) trade links with the former metropolitan power. The modernisation of the transport system in the Third World country involves, at this stage, elements of rationalisation, adaptation and selective investment in response to changing demands. There is, however, no radical adjustment to the systems inherited from earlier phases.