ADVERTISEMENTS:

Transport systems, which are operated at the global scale, are the expansion of the need for links between both individual nations and trading blocs, and have complex spatial networks. Many changes have encouraged movements on the international scale since the mid-twentieth century. Technological advances have provided us with high-capacity jet airlines, ships which carry over millions of tonnes of goods over thousands of kilometres, and movements at the global scale are now within the reach of ever-increasing numbers of people and commercial enterprises. The rapid expansion of transnational manufacturing companies in particular has also been responsible for much of the increase in international traffic.

Almost all long distance travel is now by air and the expansion of tourism has produced a demand for many additional schedule and charter service. Although international transport has several facets, which needs detailed analysis, but the present article considers the international movement of freight and passengers at various scales and by different modes, that too in the form of an introduction.

1. International Air Transport:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Although the world’s air transport networks were largely pioneered prior to World War II, the origins of mass air travel – at least in the developed world – date back no earlier than circa 1960. Since then, aggregate growth rates have been quite dramatic, albeit punctuated by short-term fluctuations caused by external events such as economic recession and the Gulf War of 1991, which severally depressed demand for air travel.

Latterly, however, the aviation industry, buoyed by increased profits resulting from the global economic upturn of the mid-1990s, remains bullish about long-term growth trends, despite concerns about fuel supplies and costs, shortages of airport capacity in many key markets, and the negative environmental impacts of air transport.

The aggregate growth in demand for air transport has been fuelled by two principal factors – growing disposable incomes in developed countries, accompanied by radical changes in the geopolitics of the industry which have resulted in government regulation and control increasingly being replaced by an ethos of deregulation, liberalisation, privatisation and increased competition.

Air transport is a high-cost mode and access to it is notably with personal wealth. There is a fair degree of correspondence between gross domestic product (GDP) and revenue passenger-kilometre (RPK). Table 10.1 shows that 90 per cent of world air scheduled, passenger and freight traffic is performed in North America, Europe and Asia-Pacific.

The United States alone accounted for 38 per cent of total passenger-kilometres performed on scheduled services, followed by UK and Japan with almost 7 and 6 per cent respectively. The largest share of international scheduled traffic – around 30 per cent is carried by European airlines, which also for the most significant single component of the world charter market.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Except, the Brazilian flag carrier – Varig, all the world’s top 30 scheduled airline groups in 1996 are based in North America, Europe or Asia-Pacific. The leading nations involved in international air traffic are USA, UK Japan and France. Trans-Atlantic and trans-Pacific routes carry the highest numbers of passengers. The general air routes of the world have been depicted in Figure 10.1.

Because of high costs of air transport, as compared with sea or land modes, air freighting is limited to valuable medicines, commodities such as electronic equipment, fashion clothing or to perishable goods such as food and flowers. The expansion of high-technology industries in the Pacific Rim, in North America and in Western Europe has generated a growing demand for air cargo services and the highest growth rates have been recorded on US-Far East routes. On an average, 740.2 million tonnes is hauled as air cargo.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The leading international airports handling over 0.5 million tonne of freight are as follows:

The general shortage of airport capacity is a fundamental impediment to the development of a more competitive airline industry. It is estimated that the world passenger air traffic will continue to rise by around 5 per cent per annum until 2010.

2. Maritime Transport:

Maritime transport carries over 75 per cent of all world trade by tonnage and 80 per cent of this is in the form of bulk traffic.

The four major categories of maritime freight are as follows:

(i) Crude petroleum, which accounted for 32 per cent of all international tonnage;

(ii) Dry bulk cargoes; principally iron ore, chemicals and grains;

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(iii) Container and other unitised traffic; and

(iv) Conventional freight, usually described as general cargo.

The transportation of crude petroleum is done through especially designed ships, i.e., tankers. World trade in crude petroleum is characterised by long-distance separation of the zones of supply and demand. The major production areas are the Middle East, the Caribbean and northern states of South America, the CIS and South-East Asia, whereas principal regions of consumption are Europe, North America, and Japan, therefore, the bulk of petroleum entering world trade is still shipped over distances involving thousands of kilometres.

Modern oil carrying vessels are now the largest vessels afloat in terms of their dead-weight tonnage, and the progressive increase in capacity has been made in order to minimise freight carriage costs. Oil tankers accounted for 33 per cent of global gross shipping with largest fleets being registered under the Liberian, Norwegian and Panamanian flags.

Dry bulk cargoes now account for about 56 per cent of tonnage of world trade. Iron ore as well other minerals, raw chemicals, coal, grain, heavy machinery, etc., are always transported through ocean routes, because of low transport costs. The introduction and expansion of maritime container traffic have produced some of the spectacular changes in vessel design and port organisation. Nowadays containers cargoes account for more than 7 per cent of total world tonnage. Container shipping is done by purpose-built ships, which carries only containers.

The major ocean trade routes of the world are as follows:

i. The North Atlantic Route:

This route links Western Europe and eastern North America.

ii. The Mediterranean-Asiatic Route:

This route connects Europe with countries of Asia, Australia, and New Zealand as well as with east African countries. The Suez Canal is the chief nodal point of this route.

iii. The Cape of Good Hope Route:

This route connects the highly industrial west Europe with Australia, New Zealand via South Africa.

iv. The European Eastern South American Route:

This route is across the Atlantic Ocean and connects Western Europe with South American countries. The other important ocean routes are: North American- East South American Route from New York to Cape Saw Rogue, North American-Western South American Route via Panama Canal, North Pacific Route (Vancouver to Yokohama), North American-Australasian Route (from New York and Vancouver to Sydney and Wellington via Honolulu), Indian Ocean Routes, etc. (Figure 10.2).

3. International Surface Passenger Transport (ISPT):

Most of the international transport is performed by air and sea routes. This has become possible because of certain international agreements between nations of the world. But, in case of land or surface transport, this has not been possible due to political barriers. Although certain railways and roads are doing this work through mutual political agreements, but that too is very limited. The best example of ISPT is the Europe, where surface transport between nations has become possible after the formation of the European Union.

Roads are the most common means of surface transport, but its importance is mostly limited to national limits. The neighbouring countries may allow or not allow international movement. It depends upon their political and strategic interests. But there are few intercontinental highways (Figure 10.3), which run across the continent. Roads of continental dimensions have also had enormous political significance ever since the old Silk Road connected the Chinese and Roman empires.

Today, the Asian Highway reaches from Istanbul to Singapore and Ho Chi Minh City. Even longer is the Pan-American Highway linking Fairbanks, Alaska with Puerto Mont, Chili, and Buenos Aires. Another international highways is the Carretera Marginal Bohvanana de la selva (commonly known as “La Marginal”) running along the eastern foothills of the Andes through Colombia, Peru and Bolivia. Trans-African highways are also important but their completion is still awaited. In European Union road transport plays a vital role.

Railways are the most important source of modern transportation, but their importance is also limited to a national limit. There are about 12.58 lakh kilometres of railway lines open for traffic in the world. But most of them are limited to the political boundary of a country. There are railways like: Trans-Siberian railway, Canadian Pacific railway, Union and Central Pacific railway, Southern Pacific railway, Cape to Cario railway, Trans-Andean railway and railways of Europe which are considered as inter-continental railways.

Europe: An Example of ISPT:

The European Union (EU) and Europe more generally, is the most important market for ISPT in the world. With relatively high disposable incomes, sophisticated trading economies, political diversity and a highly mobile but concentrated population, ISPT has experienced immense growth. In the 1980s, international traffic as a whole increased twice as fast as national traffic in the then European Community (EC).

The founding fathers of the EU recognised the importance of transport to the establishment of an integrated European economy. An important industry in its own right transport employs over 15 per cent of the Community workforce and accounts for more of the EU’s GDP than agriculture. However, it is more critical to the functioning of a truly integrated market than this figure suggests. The free movement of goods and people was a vital foundation of the Treaty of Rome (Ross, 1994), and the broad need to establish a common transport policy was acknowledged in Article 74, although progress was slow until the mid-1980s (Europa, 1996).

In the early 1980s, EC governments recognised that if the EC was to regain its competitive position in the world economy, all restrictions on the free movement of goods and people had to be abandoned. There was also, growing understanding of the penalties imposed by increasingly congested and environmentally damaging road-dominated transport infrastructure.

Furthermore, it was recognised that common policies had to replace the divergent actions of individual states. The White Paper that followed the European Council meeting at Fontainebleau in 1984 outlined a programme of legislation deemed necessary to achieve a single integrated European market. This led, through the Single European Act of 1987 – which did not refer to transport policy (Geradin and Viegas, 1993) – to the major redefinition of the Community’s objectives and modes of operation in the Maastrich Treaty, which come into effect in 1993.

The use of the term “trans-European transport network” (singular) here is significant; the EC has confirmed the importance of the “integration of land, sea and air networks”, taking account of the comparative advantages of each mode, and encouraging ‘interoperability’ within modes and ‘inter- modality’ between them.

Several other general principles have been set out as underpinnings for European transport policy into the next century. A key concept is “sustainable mobility of persons and goods”, which satisfies the Community’s aspirations in terms of “social and safety conditions”, competition, environmental protection and economic and social cohesion. The sustainable mobility theme had been adopted in a reassessment of the Common Transport Policy in 1992 (CEC, 1992), and developed more thoroughly as regards passenger transport in the Commission’s Greene Paper, The Citizens’ Network (CEC, 1996).

Two rather more cautious ideals also feature in the 1996 trans-European transport network document: that the network should “allow the maximum use of existing capacities” and “be, insofar as possible, economically viable”. Finally, the importance of connections with non-EU neighbours in recognised by a requirement that the Community’s transport networks should be “capable of connection” to those in European Free Trade Association (EFTA) states, countries of Central and Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean countries.

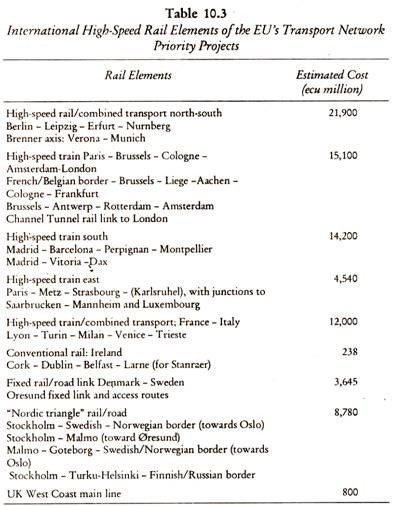

While it shares the stage with the other modes in this integrated Common Transport Policy, the Community has endorsed its desire to revive the significance of rail transport for both domestic and international transport. A prominent role is confirmed for rail in the trans-European transport network, including conventional passenger services and combined/ intermodal freight, but most prominently in the form of a comprehensive trans-European network of high-speed passenger train services. The international high-speed rail projects of EU’s transport network are given in Table 10.3.

Conclusion:

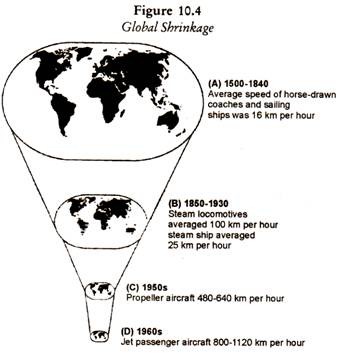

The conquest of distance by modern forms of international transport is often described in terms of ‘global shrinkage’ as shown in Figure 10.4.

In fact, transport revolution has changed the entire scenario of the international transport pattern. Advancement in shipping and aircraft technology have both stimulated and met the demands for the cheaper and more rapid movement of freight and passengers over long distances.